In about 1980 something remarkable happened in the world of tango, although it is very likely that no-one realised its significance until much later. Hector Orezzoli and Claudio Segovia, two set designers from Argentina, decided to put together a stage show about the history of tango.

The show, which was to be called Tango Argentino, was to present a history of tango from its earliest days through to its re-emergence in the 1970s. They had hoped that since tango had been such an important part of the city’s history over the previous hundred years that the people of Buenos Aires would lend their support to the project, but unfortunately this was not to be, and they struggled to raise much interest in their idea. Many of the people that had been the biggest names in tango until the 1950s had drifted away from the dance, some due to being unable to make a living from it any more, some simply due to disillusionment, and tango was starting to look less and less relevant.

Orezzoli and Segovia may have been unable to secure any investment for the show in Buenos Aires, and even found it hard to secure rehearsal space, but they were determined, and even when it looked as though the show may never go ahead they kept on with its development.

One of the main ideas that they had was to recreate some of the performances from the early years of tango and use those to show how the dance had evolved. But this proved to be harder than expected as they were surprised to find that despite cine cameras being readily available in the area and many other things being filmed at that time, there was extremely little surviving footage of tango performances available to watch. Instead Orezzoli and Segovia had to use still photographs taken at shows and milongas and piece them together one after the other to get an idea of how the performances had been presented.

For the show they recruited dancers of all ages and body types to perform as that would most closely represent the dance scene they were trying to portray. The dancers were invited to choreograph their own routines, and many of them ended up improvising them on the night. Most of them were – or had been – well known tangueros and tangueras of their time, but some relatively unknown dancers were included as well.

Although the show’s creators were both well known set designers, the set itself was kept simple. They used one layout for the stage for the whole production, and the changes of mood were achieved with lighting and through the performances themselves. This kept costs down, but also ensured the focus of the audience would always be on the dancers and the dance. The tango was to be the star of the show and the simple staging presented it to the audience without distractions.

When they had originally come up with the concept for the show a few years earlier they had hoped to use the orchestra of Aníbal Troilo to provide the music. But unfortunately Troilo had died in 1975, and so they recruited Horacio Salgán and the band Sexteto Mayor instead. This band consisted of one piano, one double bass, two violins and two bandoneóns, and was a similar format to the orquesta tipica of the early tango years but with slightly fewer musicians.

Despite years of effort in putting the show together and with all the people involved in developing the routines, Orezzoli and Segovia could still not find anywhere willing to host Tango Argentino. But then in 1983 they were invited to put on a performance at the Festival d’Automne being held in the Centre Pompidou in Paris. So they boarded the only aeroplane they could afford – a military transport – and flew to France.

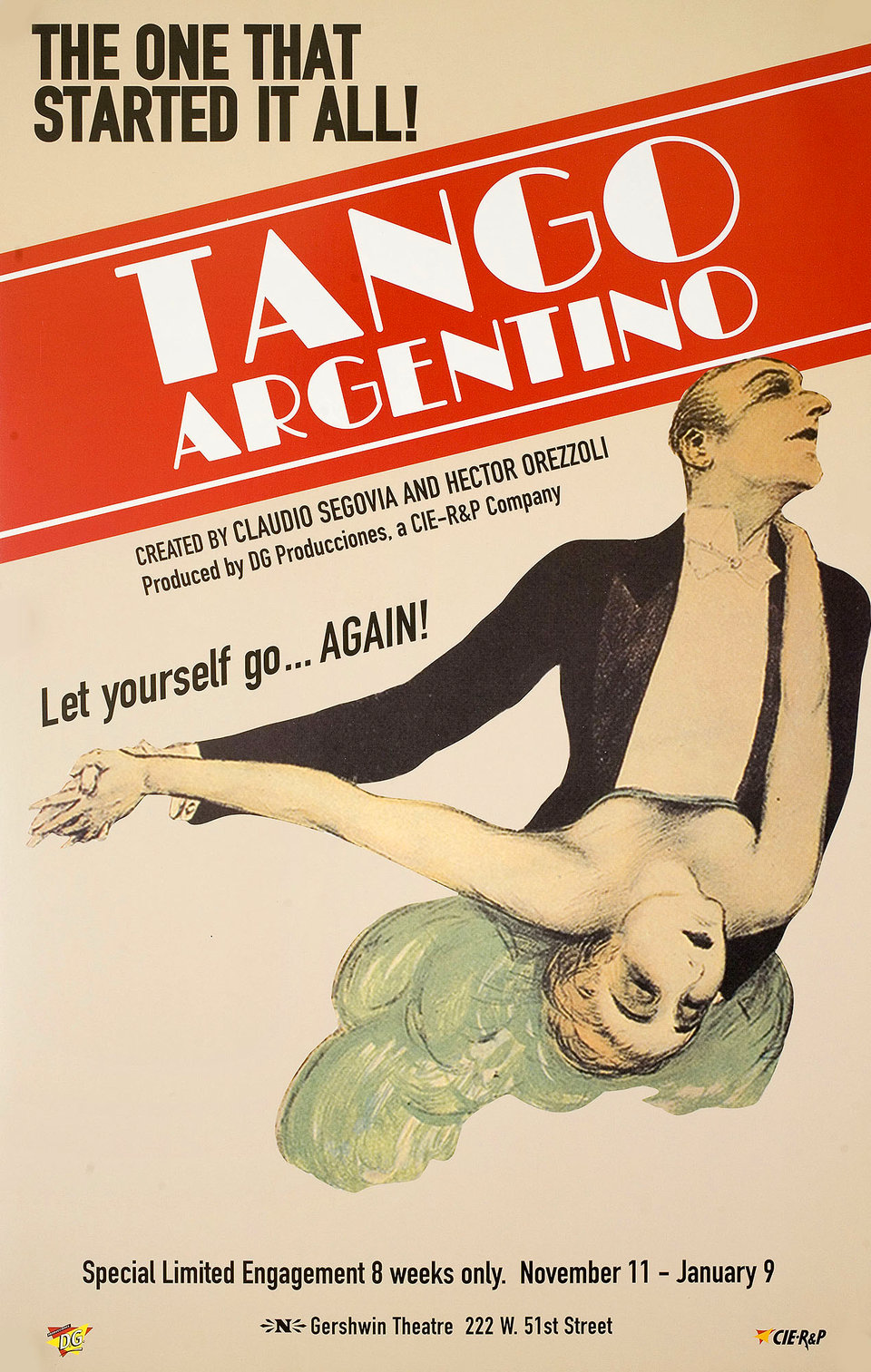

Tango Argentino

The show was an unexpected success. When people saw it they were captivated and from its first performance it received standing ovation after standing ovation. Audiences went home talking about tango and demanding to know where they could see more of this dance or maybe even try it themselves. Almost overnight it ignited a huge new demand for tango everywhere the show was performed, and suddenly the Argentine tango community was back in the spotlight. Success bred success, and Tango Argentino began to tour the world:

- 1983 – France

- 1984 – Italy

- 1985 – New York

- 1985-1986 – US and Canada

- 1987 – Japan

- 1988 – Europe

- 1991 – United Kingdom

- 1992 – Buenos Aires

- 1999-2000 – A revival on Broadway (New York)

Wherever the show was performed tango fever struck. Audiences were captivated by the diversity of dance styles and the varied interpretations of the music by the dancers. The mix of young and athletic dancers with older and more “normal” body types resonated with those who watched the show, and everyone who watched it wanted to find out more about this incredible dance. They all saw someone in the show who looked like them, and so instead of simply seeing it as an incredible virtuoso showcase, they also thought “I could do that!”

This new international interest in tango fuelled the rebirth of the dance in Buenos Aires itself, and the old maestros who had been dancing in the Golden Age began to come out of retirement. People started travelling to the city from all over the world to go and study with the maestros, and they in turn soon began travelling to Europe, America, and beyond to spread their knowledge and experience of tango far and wide. They would dance demonstrations, teach workshops, train other teachers, and within a very short time the tango phenomenon had spread around the globe.

Legacy

Although no-one could have predicted it before the event, the show left a powerful legacy. Tango had been fading for years, falling into irrelevance and becoming little more than a historical footnote even in its own hometown. But Tango Argentino not only created a huge amount of interest in the dance in the cities where it was performed, it also revitalised the tango community in Buenos Aires and created a new tango tourism industry from nothing.

In every city where the show appeared there soon rose a demand for tango social events – milongas – to be run. People not only wanted to see tango being performed, they wanted to be a part of it, to dance it themselves and to recreate what they had seen on stage. And so the first milongas that started to appear modelled themselves on what had been seen in the show. The music that was played came directly from the dance halls of 1940s Argentina, with the scratchy recordings evoking a time when tango was at its peak. This was music from the Golden Age as it came to be known. The period from 1933 to the early 1950s when the great tango orquestas tipica were performing in bars and clubs around Buenos Aires and Montevideo.

In London the first milonga to emerge from the new wave of tango popularity was a Friday night event called Tango, The Argentine Way held in the London Welsh Centre on Gray’s Inn Road. This was started in the early 1990s by Andrew Potter, an Argentine-British dancer who had followed the tour of Tango Argentino (and a subsequent show called Forever Tango) and knew that such an event would be popular. His event not only ran as a weekly milonga, but also brought in dancers and maestros from Buenos Aires to teach and inspire the attendees. From there the word spread, and within a very short period of time there were tango clubs, classes, workshops, and performances appearing all over London and beyond.

Tango had arrived in London in a big way, and the manner of its arrival was to have a dramatic impact on how tango would be taught and interpreted over the years to come.

The purpose of the show Tango Argentino was to be a historical retrospective of how tango had emerged and evolved from the late 1800s to about 1970. It included references to how people danced and the music being played, but it also presented a view of Argentine society that was specific to that time period. During the early years of tango the Great European Immigration Wave was in full flow, and as a result there were far more men around than women. Strict social rules came into being to ensure “proper behaviour” at the milongas, and these rules then began to be incorporated into tango itself. I will talk about those rules – the codigos – in a later chapter, but for now it is enough to say that the codigos are extensive, all-encompassing, and breaking them can see you ejected from the milonga faster than you can say “ocho cortado”.

When the first milongas appeared, such as Tango, the Argentine Way, the codigos were implemented there as well. It helped promote the idea that tango was a little different to other dances. It suggested that it harkened back to a more romantic time, and much like a modern tea dance with big band music from Glenn Miller and Tommy Dorsey it was also a period re-enactment of what it must have been like to have been there when it all began.

The subsequent proliferation of milongas over the next few years followed the same pattern, and although they may not all have gone for the full re-enactment experience, most of them implemented some or all of the tango codigos at their events. Today the codigos are often taught as part of regular classes, and so their inclusion continues.

Proliferation

There is no doubt that tango in the UK and in many other countries around the world owes its existence to the wave of popularity that resulted from the show Tango Argentino. Without those performances it is likely that the only tango we would know about now are the ballroom variants of the dance with their strict regulation and choreographed routines. We would never have come to see the fluid, interpretative, improvisational style that is the hallmark of the tango we know and love, and the world would have been poorer without it.

Tango’s return by way of a retrospective show meant that it came with links to a set of rules that had been designed to meet the needs of a different place and a different time. This set tango apart from many other dance styes and lent it an air of exoticism and something romantic that even the ballroom dances with their big band music and stylised outfits could never quite match. It paved the way for tango to flourish and opened doors that otherwise may have stayed closed, but it also created the opportunity for a unique tension in the tango world that does not appear in most other dance styles.

For some, tango was a chance to experience and absorb the atmosphere of those early Golden Age clubs and milongas. The music and the dance were inextricably linked and one could not be experienced without the other. The rules, the culture, and everything that went with tango must be preserved, for to change anything was to disrespect the significance of tango to the culture and history of Buenos Aires.

For others, however, the rebirth of tango was an opportunity to allow it to continue its evolution as though it had never stopped. New musical styles and new dance techniques could be used, and tango now had the chance to be brought up to date as we approached and moved into the next century.

No responses yet